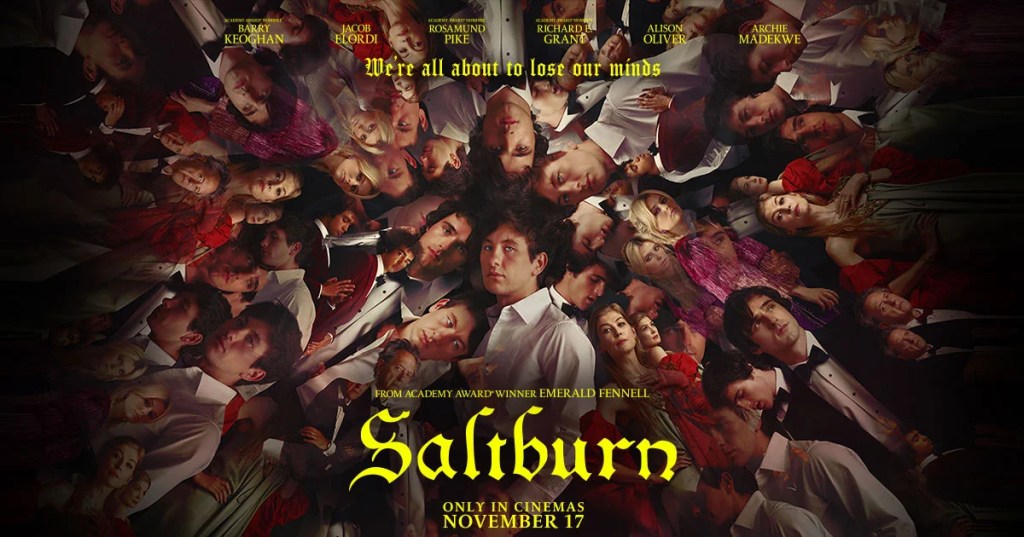

This deliciously dark and decadent film rather unpredictably achieved meme status on social media early in 2024, shortly after its release on Amazon Prime. I suspect the TikTok algorithm had me well and truly figured out but every second or third video I was served was Saltburn-inspired. If it wasn’t some mischievous teenager tricking their grandparents into watching that bathtub scene, or that grave scene, it was a (clothed) recreation of Barry Keoghan’s indulgent rhythmic romp around Saltburn Manor by some privileged teenager whose parents own a house bigger than anybody really needs. I am slightly ashamed to confess that I’ve now seen Saltburn no less than four times. I saw it at the cinema in November 2023. I went into it more or less blind, having seen only the trailer. Boy, was I in for a treat. I’ve then watched it a further three times – once with my very unfortunate girlfriend, who didn’t thank me at all – on Amazon Prime. I love it. But it’s one of those films you don’t tell people you love, lest they conclude you’re some sort of psychopath or weirdo. Psychopath…that’s a word…

Let’s start with those memorable scenes. The vampire scene. Wowzer. I saw an interview with Emerald Fennell, the writer and director, in which she suggested that this was a beautiful scene. They do say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Neither of my eyes have a particular fondness for menstrual cunnilingus but I’m just one man. Fennell’s reasoning is that this is Oliver conveying to Venetia his absolute acceptance of her. His acceptance of her body as it was. For a bulimic, this was no doubt a profoundly powerful gesture and it’s not difficult to believe that Oliver, an accomplished and motivated manipulator, knew precisely what he was doing. The scene is visceral and, some might say, a little bit gross. But those closing their eyes and turning away in disgust risk missing something significant: Farleigh voyeuristically staring out of the window at Oliver and Venetia. Why is this significant? Well, it’s the only occasion in the entire film where we ostensibly see something happening of which Oliver is seemingly unaware. Every other scene revolves around Oliver. Even that heated conversation between Farleigh and Felix is one which Oliver is eavesdropping in on. But Felix and Venetia’s encounter, Farleigh supposedly witnesses clandestinely. Or does he? I think not. Oliver knew what he was doing. Bathed in moonlight – a full moon, no less – and within view of Farleigh’s window. Oliver was not overcome by lust. He didn’t forget himself. He knew what he was doing and he knew Farleigh was watching. It was another one of Oliver’s spidery webs.

The bathtub scene. Infamous. It has even spawned an array of merchandise, guaranteed to induce mild to moderate nausea. Do you lap the last few drops of java out of your coffee cup like a thirsty rotund Labrador drinks from its water bowl after a longer-than-usual weekend walk? Maybe this mug is for you. Do you have a friend who enthusiastically believes in the restorative qualities of aromatherapy? How about a salty cream candle? Can’t quite find the words to express the love you hold for your significant other? Say it with a card. Hallmark are sleeping on that one. What’s interesting about this scene is that, much like the grave scene (I’m getting to it), it’s not for anybody’s benefit other than Oliver’s. This is the Oliver conundrum. The easiest conclusion to reach is that Oliver must be a psychopath, driven by greed and a thirst (see what I did there?) for power. I’m not entirely convinced it’s as simple and I think there’s more to Oliver than this. Guzzling dirty semen water is not necessarily psychopathic. It’s bizarre. But I’m not entirely sure it’s psychopathic. Or maybe it is. Maybe this was Oliver’s attempt to possess and own Felix in some Dahmer-esque fashion, hungrily consuming what he could of his little swimmers to keep Felix’s DNA with him always. Crikey. Gross. It’s the slurping and guzzling noises for me. I bet some absolute weapon has made an ASMR out of that.

The grave scene. There are many things in Saltburn for which Fennell bears absolute responsibility. This scene is not one of them. It was improvised by Keoghan. Now, I like Keoghan. I thought he was masterful in The Killing of a Sacred Deer. I think he’s a top chap. But I can’t help but question the inner-workings of his mind, knowing that the grave scene was his brainchild. What made him drop his kegs and fornicate with a mound of John Innes’ finest? It’s another scene for Oliver’s benefit and nobody else’s. There’s a moment during Venetia’s bathtub monologue (an awful lot happens in bathtubs in this film) where there’s the suggestion she’s witnessed Oliver’s graveside aberration but, alas, she didn’t. Probably for the best, really. It’s another scene that, I’d say, undermines the suggestion that Oliver is a common-or-garden variety psychopath. Or does it? I’m still on the fence with this. Maybe I’m leaning into the reptilian psychopath stereotype a little too hard here.

Who and what was Oliver? Needless to say he is a deeply complex character who, for the first two thirds of the film, conceals his true motivations (whatever they may be) beneath a stodgy layer of artifice, feigning vulnerability, innocence and social awkwardness. He appears utterly harmless, to the extent that one might be forgiven for initially anticipating his imminent demise at the hands of the Catton family. This is no accident. The “strange butler trope”. A cavernous stately home, set on the grounds of a seemingly isolated country estate. And a sense that this family, steeped in opulence, privilege and vast generational wealth, must have malign intent. What do they want with Oliver? Why have they lured him here? Is this some satanic, Wicker Man deal? Is Oliver a blood sacrifice? Are they going to drink his hot, thick, blood from an altar in their private cemetery?

It is not until Felix’s death that we start to see the Catton family for what they really are – “dogs sleeping belly up”, as Oliver says. Despite – and because of – their immense social capital and wealth, they are profoundly weak. They have not struggled in the face of adversity. They live in an airbrushed world of their own curation. Never mind the silver spoons, they were born with the entire ivory-handled, sterling silver, eighteenth century cutlery set in their hungry mouths. The response to Felix’s death is intentionally bizarre. This is a family which navigates high society with ease and subscribes without question to its rules. They keep up appearances. When the news of Pamela’s passing reaches Saltburn, the family are seemingly unaffected. When Farleigh is wrongfully accused of thievery and expelled from Saltburn, nothing is said. When Felix dies, Sir Richard’s extreme insistence on normality is nothing short of jaw-dropping. The family tries, and fails, to eat lunch. We see the limits of their enforced emotional repression. Venetia overfills her wine glass, leaving a pool of claret on the table (a prescient nod to what is to come, perhaps), and Farleigh turns on Oliver.

So what did they want with Oliver? Was he a charity case? Some light entertainment? Elspeth certainly seems to derive a sort of grim joy from revelling in Oliver’s misfortunate childhood. We see her and Pamela enthusiastically, and without restraint, discussing his parents’ addictions at considerable volume when he arrives at Saltburn. We know that Felix had a previous guest stay at Saltburn who was unceremoniously expelled after an intimate encounter with Venetia – a fate Oliver narrowly avoided himself. Were they hoping that Oliver’s struggles, much like Pamela’s, might break the monotony of privilege? The Cattons have everything they could want. They strive for nothing. Privileged as they may be, their lives are boring. One can’t help but wonder if these poor unfortunates are occasionally imported to inject some life into the otherwise stale and musty Saltburn estate. When it transpires that the tale of Oliver’s sad childhood is just that, his own expulsion from the Saltburn estate is swiftly arranged. He ceases to be interesting or entertaining. Was this Oliver’s trigger? Or was he always intent on following a murderous path? That is the question.

Some have speculated that Oliver would never have done what he did had Felix not rebuffed him and it is this question that really brings into focus the complexity of Oliver’s character. He tells us that he loved Felix. He was not in love with Felix but he loved him. He wasn’t in love with him, but he humped his grave, watched him engaging in intimate acts, and very hungrily imbibed his seed. The big reveal, as Oliver pulls Elspeth’s plug, reveals the extent of Oliver’s Machiavellian scheming. He deviously manipulated Felix to strike up a friendship with him and, once he had him caught in his web, set about tightly cocooning him like a spider would its prey. He identifies that – by playing the vulnerable down-and-out and the social outcast – he can win Felix’s affection. Quite how he knew Felix would be vulnerable to such an approach is unclear. Was it psychopathic instinct? Or did he know of Felix before he arrived in Oxford? Who knows.

On a final note, the dynamic between Oliver and Elspeth must be recognised. It is one of the most important in the film. It is Elspeth, and her affection for Oliver, which keeps Oliver in the fold. We know from Venetia’s bathtub monologue that Sir Richard had already begun to figure Oliver out and, of course, he is ousted from Saltburn after Venetia’s death. But such is the strength of the affection Elspeth has for Oliver that Sir Richard needs to pay Oliver off to have him leave quietly. What is the source of that affection? One line. The most important line of the film, in my view.

Because you’re so fucking beautiful.

Elspeth detests ugliness. She tells us as much. She is judgemental, intolerant and vain. With that one sentence, Oliver wins Elspeth’s loyalty. Elspeth feeds on the ugliness of other’s lives. Oliver’s tragic childhood. Pamela’s woes. As much as she might detest ugliness, she surrounds herself with it to hide from the realisation that she herself might just be ugly. I wouldn’t do Rosamund Pike dirty like that but Elspeth certainly has an ugly soul. Elspeth’s singleminded sprint from the ugly towards the beautiful left her vulnerable to Oliver. This is, in my view, a film about the fallibility of beauty and the vulnerability of those who chase aesthetic gratification.

Leave a comment